Functional and parallel PageRank implementation in Scala

When I came back to Equisense, I was surprised and intrigued by many things. But there was one element of the job in particular I had not planned: coming back to low level and embedded programming from higher abstractions I was used to. No OS, no libraries, no smooth write-and-test work-flow, just brutal and bare metal. I clearly needed to blow some steam off with something closer to what I usually do (or did), a data-driven and functional project using nice techs.

Why yet another PageRank?

The time came to find a new side project and I was just finishing the lectures of Parallel Programming, which I recommend if you’re already at ease with Scala and its environment (IDEs, SBT). I wanted to apply the concepts on a project built from scratch. One day, while neglectfully scrolling through another blog post showing the basic concepts of the PageRank computation, I thought this would make a “okay” project. But wait, interesting elements here:

- The model behind the PageRank computation is a Markov Chain, with which I have been working a lot with at Siemens.

- Iterating until stability of the ranks is basically a linear flow, easily

performed by tail call recursion

which is optimized to avoid stack-overflowing the JVM by behaving like a

whileloop. - Computing the rank of each site is independent of the other computations, parallelizing the tasks is a piece of cake

So we’re all set up for a purely functional and parallel PageRank.

The PageRank model

We’re gonna go through the basic implementation of the algorithm. What fascinates me is the two-sided view of the algorithm: the intuitive version can be explained to a 5-year-old (or to your boss) while the maths behind it relies on the interpretation of matrix eigenvalues and on a computation of the stationary distribution of the Markov model.

The intuitive version

Imagine you’re surfing on the web like any productive Sunday evening. On a given page, there is an equal probability to click on any link present on the page. There is also a probability that you get tired of the current series of pages and randomly go back to any page of the network.

Let’s try to visualize the two extremes of this “random switch” usually called

damping factor d. If we set d=0, the transition to any page is equally

probable, since the surfer will always switch to choosing a page at random.

This means that the links going out of the page they’re currently on don’t

influence the probability distribution of the next page.

On the other end of the spectrum if the damping factor d=1, the surfer will

always look for its next page in the outgoing links of her current page

(this raises an issue for pages without any links). An usual value for the

factor is d=0.85which keeps the probability of long sequences of related pages

likely to happen, but allows for random switch.

Key elements of the algorithm

The algorithm uses the matrix of links: an entry (i,j) is 1 if there is a

link on the page j to the page i and 0 otherwise (note that this notation

is opposite to the common convention for Markov transition matrices, where the

line is the origin state and the column the destination). The other element is

a rank vector which is updated until a convergence criterion is met.

Types of the different structures

Since we want to be able to perform some computations in parallel, most functions will manipulate Scala’s Generic data structures. Let’s start with the link matrix. It is a sparse structure: instead of representing all entries of the matrix in a vector of vectors, just non-empty elements and there corresponding column and line indexes are stored.

// defining a dense matrix of Ints as a sequence of sequence

type DenseMatrix = GenSeq[GenSeq[Int]]

// SparseMatrix: tuple (line, column, value)

type SparseMatrix = GenSeq[(Int,Int,Int)]However, the values of our link matrix only contains zeros and ones, so the entries present in the structure all have one as value, so we just need to keep rows and columns:

type LinkMat = GenSeq[(Int,Int)]The ranks are stored in a simple generic float sequence:

R: GenSeq[Float]We also need a few utility functions. sumElements takes the matrix, the rank

vector and an integer to find all links for which the outgoing page is j.

def sumElements(R: GenSeq[Float], A: LinkMat, j: Int): Float = {

// sums all PageRanks / number of links for a column j

val totalLinks = A.filter{tup => tup._2 == j}

if (totalLinks.isEmpty)

sys.error("No link in the page " + j + " at sumElements")

else

R(j)/totalLinks.size

}Note This implementation of the function is not purely functional since

an imperative system error is raised if no index i is found. A better solution

here would have been to wrap the value in an Option[Float], return None if no

index has been found and Some(x) in case of success.

We also need to find all pages pointing to a given page i. This might be a bit compact, but keep in mind that the matrix is simply a pair of page indexes. So we find all pages where the first element is i (the page the link is going to), that’s the filter part. We then take the second element of the tuple, so all indexes pointing to i, thanks to a map.

def findConnected(i: Int, A: LinkMat): GenSeq[Int] =

A.filter(_._1==i).map(_._2).toSeqNote that the result is returned as a normal sequence (not the generic version allowing for parallel computation). It’s not a big deal since the resulting sequence is always manageable compared to the whole graph we are manipulating.

Now, we stated that the algorithm recurses on the rank of all pages until

stability, which is something we define through a converged function. We

simply use a squared difference between two different versions of the rank to

determine if they are acceptably close and yield a boolean.

def converged(r1: GenSeq[Float], r2: GenSeq[Float], eps: Float): Boolean = {

val totSquare: Float = r1.zip(r2).map(p=>(p._1-p._2)*(p._1-p._2)).sum

sqrt(totSquare/r1.size)<=eps

}Now that everything is set, the master piece becomes a piece of cake.

@tailrec def compRank(R: GenSeq[Float], A: LinkMat,

damp: Float, eps: Float,

niter: Int = 0,

niterMax: Int = 10000): GenSeq[Float] = {

val rankIndex: GenSeq[Int] = 0 until R.size

val rightRank: GenSeq[Float] = rankIndex map{i:Int =>

val connected = findConnected(i,A)

connected.map{j:Int => sumElements(R, A, j)}.sum

}

val newRank = rightRank map {damp*_ + (1-damp)/R.size}

if(converged(newRank,R,eps)) newRank

else if(niter>=niterMax) {

println("Max iteration reached")

newRank

} else compRank(newRank,A,damp,eps,niter+1,niterMax)

}We first compute the right term of the new rank formula rightRank and plug it

in newRank. The two vectors can be passed to compare to determine if

newRank can be returned as a final result or if further recursion is needed.

A recursion counter also avoids waiting too long for a result and warns in case

of maximum recursion reached by printing to the standard output.

Once again, a more functional way would have been to wrap the result in a

Try monad (no panic, we’re NOT going to go through monads, we’ve lost enough

people with this).

You’ve surely noticed the @tailrec tag highlighting that this function is not

going to blow the stack up.

Result on a study case

The Enron email dataset

While surfing in a semi-random way to find a cool dataset for the application, I found the SNAP project from Stanford on which the Enron emails data are presented and to be downloaded. If you look at the Github repo for this project, I simply removed the header from the txt file to make the parsing tasks easier.

Results

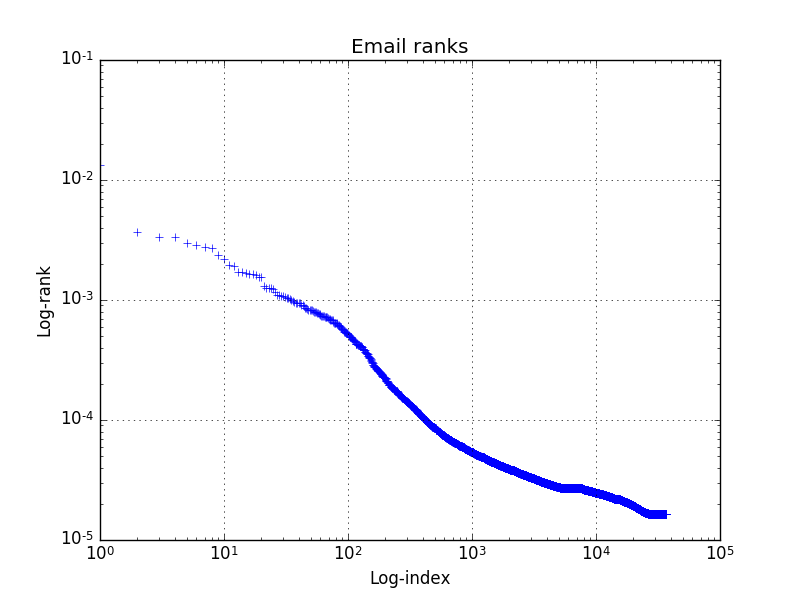

As many phenomena dealing with concentration of resources,

the distribution of ranks follows a Pareto distribution, which can be

visualized on a log-log scale. I used Python with numpy and matplotlib, finding

the current Scala libraries still to cumbersome for this simple task. Here is

the result:

A conclusion on the functional/imperative debate

If some of you clone and try to run the project (you’ll just need sbt for that). Some people could argue that the runtime is too long for what it does (whatever too long means), and that an imperative solution with a mutable rank on which we loop until convergence. And I suppose they are right, but parallel imperative is objectively a pain to work with. Tell the architecture what you want, not what to do and it will compute it for you, whatever its configuration is, from your laptop to several clusters. That’s a key reason why Spark is functional for instance.