Solving the group expenses headache with graphs

With the end-of-year celebrations, we all had some expenses to manage, some of them shared with friends, and we all have this eternal problem of splitting them fairly.

Les bons comptes font les bons amis. French wisdom

Applications like Tricount or Splitwise became famous precisely by solving this problem for you: just enter the expenses one by one, with who owes whom and you’ll get the simplest transactions to balance the amounts at the end.

In this post, we’ll model the expense balancing problem from a graph perspective and see how to come up with a solution using Julia and the JuliaGraphs ecosystem [1].

Table of Contents

The expenses model

Say that we have $n$ users involved in the expenses. An expense $\delta$ is defined by an amount spent $\sigma$, the user who paid the expense $p$ and a non-empty set of users who are accountable for this expense $a$.

$\delta = (\sigma, p, a)$

The total of all expenses $\Sigma$ can be though of as: for any two users $u_i$ and $u_j$, the total amount that $u_i$ spent for $u_j$. So the expenses are a vector of triplets (paid by, paid for, amount).

As an example, if I went out for pizza with Joe and paid 8GPHC for the two of us, the expense is modeled as:

$\delta = (\sigma: 8GPHC, p: Mathieu, a: [Mathieu, Joe])$.

Now considering I don’t keep track of money I owe myself, the sum of all expenses is the vector composed of one triplet:

$\Sigma = [(Mathieu, Joe, \frac{8}{2} = 4)]$

In Julia, the expense information can be translated to a structure:

const User = Int

const GraphCoin = Float16

struct Expense

payer::User

amount::GraphCoin

users::Set{User}

endReducing expenses

Now that we have a full representation of the expenses, the purpose of balancing is to find a vector of transactions which cancels out the expenses. A naive approach would be to use the transposed expense matrix as a transaction matrix. If $u_i$ paid $\Sigma_{i,j}$ for $u_j$, then $u_j$ paying back that exact amount to $u_i$ will solve the problem. So we need in the worst case as many transactions after the trip as $|u| \cdot (|u| - 1)$. For 5 users, that’s already 20 transactions, how can we improve it?

Breaking strongly connected components

Suppose that I paid the pizza slice to Joe for 4GPHC, but he bought me an ice cream for 2GPHC the day after. In the naive models, we would have two transactions after the trip: he give me 4GPHC and I would give him 2GPHC. That does not make any sense, he should simply pay the difference between what he owes me and what I owe him. For any pair of users, there should only be at most one transaction from the most in debt to the other, this result in the worst case of $\frac{|u| \cdot (|u| - 1)}{2}$ transactions, so 10 transactions for 5 people.

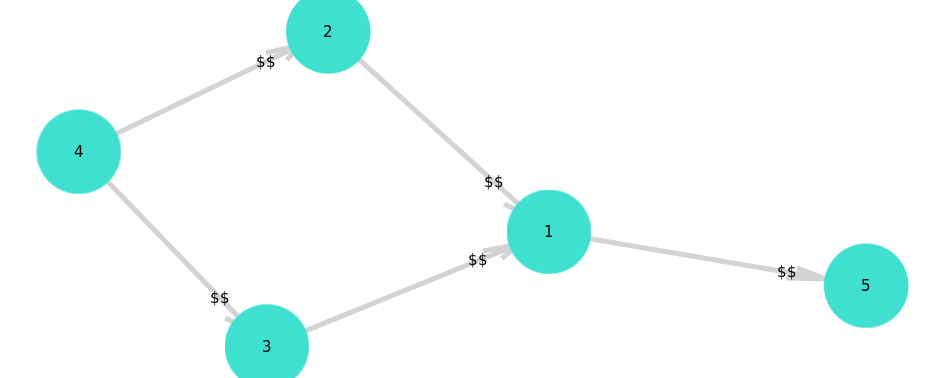

Now imagine I still paid 4GPHC for Joe, who paid 2GPHC for Marie, who paid 4GPHC for me. In graph terminology, this is called a strongly connected component. The point here is that transactions will flow from one user to the next one, and back to the first.

If there is a cycle, we can find the minimal due sum within it. In our 3-people case, it is 2GPHC. That’s the amount which is just moving from hand to hand and back at the origin: it can be forgotten. This yields a new net debt: I paid 2GPHC for Joe, Marie paid 2GPHC for me. We reduced the number of transactions and the amount due thanks to this cycle reduction.

Expenses as a flow problem

To simplify the problem, we can notice we don’t actually care about who paid whom for what, a fair reimbursement plan only requires two conditions:

- All people who are owed some money are given at least that amount

- People who owe money don’t pay more than the net amount they ought to pay

We can define a directed flow network with users split in two sets of vertices, depending on whether they owe or are owed money. We call these two sets $V_1$ and $V_2$ respectively.

- There is an edge from any node of $V_1$ to any node of $V_2$.

- We define a source noted $s$ connected to all vertices in $V_1$, the edge from $s$ to any node of $V_1$ has a capacity equal to what they owe.

- We define a sink noted $t$ to which all vertices in $V_2$ connect, with infinite capacity and a demand (the minimal flow that has to pass through) equal to what they are owed.

With this model, GraphCoins will flow from user owing money to users who are owed money, see Wikipedia description of the flow problem.

Computing net owed amount per user

Given a vector of expenses, we should be able to build the matrix holding what is owed in net from a user to another:

"""

Builds the matrix of net owed GraphCoins

"""

function compute_net_owing(expenses::Vector{Expense}, nusers::Int)

owing_matrix = zeros(GraphCoin, nusers, nusers)

# row owes to column

for expense in expenses

for user in expense.users

if user != expense.payer

owing_matrix[user,expense.payer] += expense.amount / length(expense.users)

end

end

end

# compute net owed amount

net_owing = zeros(GraphCoin, nusers, nusers)

for i in 1:nusers-1

for j in i+1:nusers

if owing_matrix[i,j] > owing_matrix[j,i]

net_owing[i,j] = owing_matrix[i,j] - owing_matrix[j,i]

elseif owing_matrix[i,j] < owing_matrix[j,i]

net_owing[j,i] = owing_matrix[j,i] - owing_matrix[i,j]

end

end

end

return net_owing

endFrom that matrix, we should determine the net amount any user owes or is owed:

"""

What is owed to a given user (negative if user owes money)

"""

function net_owed_user(net_owing::Matrix{GraphCoin})

return (sum(net_owing,1)' - sum(net_owing,2))[:,1]

endThe sum function used with 1 or 2 sums a matrix over its rows, columns

respectively. This computes a difference between what a user is owed and what

they owe.

Building the graph and the corresponding flow problem

A flow problem is determined by the directed graph (nodes and directed edges), the minimal flow for any edge, a maximal flow or capacity for any edge and a cost of having a certain flow going through each edge.

First, we need to import LightGraphs, the core package of the JuliaGraph ecosystem containing essential types.

import LightGraphs; const lg = LightGraphs

Note that I use explicit package import (not

using), an habit I kept from using Python and that I consider more readable than importing the whole package into the namespace.lghas become my usual name for the LightGraphs package.

function build_graph(net_owing::Matrix{GraphCoin})

nusers = size(net_owing,1)

g = lg.DiGraph(nusers + 2)

source = nusers + 1

sink = nusers + 2

net_user = net_owed_user(net_owing)

v1 = [idx for idx in 1:nusers if net_user[idx] < 0]

v2 = [idx for idx in 1:nusers if net_user[idx] >= 0]

capacity = zeros(GraphCoin, nusers+2,nusers+2)

demand = zeros(GraphCoin, nusers+2,nusers+2)

maxcap = sum(net_owing)

for u1 in v1

lg.add_edge!(g,source,u1)

capacity[source,u1] = -net_user[u1]

for u2 in v2

lg.add_edge!(g,u1,u2)

capacity[u1,u2] = maxcap

end

end

for u2 in v2

lg.add_edge!(g,u2,sink)

capacity[u2,sink] = maxcap

demand[u2,sink] = net_user[u2]

end

(g, capacity, demand)

endThis function builds our graph structure and all data we need attached.

Solving the flow problem

Now that the components are set, we can solve the problem using another component of the JuliaGraphs ecosystem specialized for flow problems:

using LightGraphsFlows: mincost_flow

using Clp: ClpSolver

We also need a Linear Programming solver to pass to the flow solver, all we have to do is bundle the pieces together:

function solve_expense(expenses::Vector{Expense}, nusers::Int)

(g, capacity, demand) = build_graph(compute_net_owing(expenses, nusers))

flow = mincost_flow(g, capacity, demand, ones(nusers+2,nusers+2), ClpSolver(), nusers+1, nusers+2)

return flow[1:end-2,1:end-2]

endWe truncate the flow matrix because we are only interested in what users

are paying each other, not in the flows from and to the source and sink.

Trying out our solution

Now that all functions are set, we can use it on any expense problem:

expenses = [

Expense(1, 10, Set([1,2])),

Expense(1, 24, Set([1,2,3])),

Expense(3, 10, Set([2,3]))

]

solve_expense(expenses, 3)3×3 Array{Float64,2}:

0.0 0.0 0.0

18.0 0.0 0.0

3.0 0.0 0.0

In the result, each row pays to each column and voilà! Our three users don’t have to feel the tension of unpaid debts anymore.

Conclusion, perspective and note on GPHC

We managed to model our specific problem using LightGraphs.jl and the associated flow package pretty easily. I have to admit being biased since I contributed to the JuliaGraphs ecosystem, if your impression is different or if you have some feedback, don’t hesitate to file an issue on the corresponding package, some awesome people will help you figure things out as they helped me.

There is one thing we ignored in our model, it’s the number of transactions realized. Using this as an objective turns the problem into a Mixed-Integer Linear Programming one, which are much harder to solve and cannot use simple flow techniques. However, I still haven’t found a case where our simple approach does not yield the smallest number of transactions.

Final word: I started the idea of this article long before the crypto-madness (September actually), when currencies where still considered as boring, nerdy or both, sorry about following the (late) hype. I even changed GraphCoin symbol to GPHC because I found another one with which my initial name conflicted.

If you have questions or remarks on LightGraphs, LightGraphsFlows, the article or anything related, don’t hesitate to ping me!

Edits:

Special thanks to Seth Bromberger for the review.

The cover image was created using GraphPlot.jl.

[1] James Fairbanks Seth Bromberger and other contributors. Juliagraphs/LightGraphs.jl: Lightgraphs, 2017, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.889971. DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.889971