A naive and incomplete guide to peer-review

After the first submissions to journals, most researchers will be contacted by editors for reviewing articles others have written. It may seem like a daunting task, evaluating the work someone else put several months to prepare, code, write, correct and submit.

Disclaimer: to preserve the anonymity of the reviews I made and am making, all examples I give below are made up.

The main phases of my reviewing process are:

- What is this about? Can I review it?

- Is the paper in the scope of the journal?

- Are there some topics I might struggle to understand?

- Diving in, a first pass to get the story right

- Thematic passes & writing the recommendations

What is this about? Can I review it?

After receiving the invitation and getting the manuscript, my screening phase consists in reading only these three elements:

- Title

- Abstract

- Keywords

At that point, I roughly know if it is relevant for both the journal and me that I review it. If I feel way out of scope, I’ll reach out to the editor. I will also quickly check the name of the authors to make sure I do not have a conflict of interests with any of them, without looking them up on the internet of course, the goal is to avoid bias if I know them at a personal level.

Note: Since this only took a quick screening, it can be done in a day or two, letting the editor know too late that you will not review increases the time to publication which is bad for the author, the journal and scientific publication in general.

Is the paper in the scope of the journal?

At that point, I re-read the journal’s aim and scope and keep in mind the main ideas. If I am not that familiar with it, I will also check titles and abstracts of random papers in the last issues. This will help during the review if there are some doubts on the manuscript being at the right spot.

Are there some topics I might struggle to understand?

If I have doubts on some parts of the method or context and can identify them, I’ll search for foundational articles and reference text books on the subject.

In any case, it is predictable that not all reviewers of the paper cover the same area of expertise, especially for multi-disciplinary journals. Still, it is always better to be comfortable with all components. Take a case in mathematical optimization, for instance a manuscript tackling a problem in power systems, with a game theoretical aspect and formulating a Semi-Definite Positive model solved using a bundle method. I might be familiar with the application (power systems) and game-theoretical considerations in such domain, but without being an expert in SDP and even less bundle methods. This is not a reason to refuse the role of reviewer.

However, not being proficient on a component can introduce a bias in the review by putting the reviewer on the defensive:

“why do the authors need all this fuss with this thing I’ve never heard of, why not the good all techniques like what I do”.

I’ve seen read different comments in reviews which looked a lot like this. This is why it can be valuable to take some time to get more familiar with shadow areas. Plus this makes reviewing a challenge and an excuse to learn something new and connected to my area.

Diving in, a first pass to get the story right

At that point, I book at least two hours for a first read of the paper,

with a pen, a printed version and a notebook. I should eventually get a

tablet to take notes on the PDF instead of print-outs but for the moment,

the number of papers I am asked to review remains reasonable.

I read it through without interruptions (no phone, no open browser, no music

or music without lyrics), taking notes on the side on all things that cross

my mind.

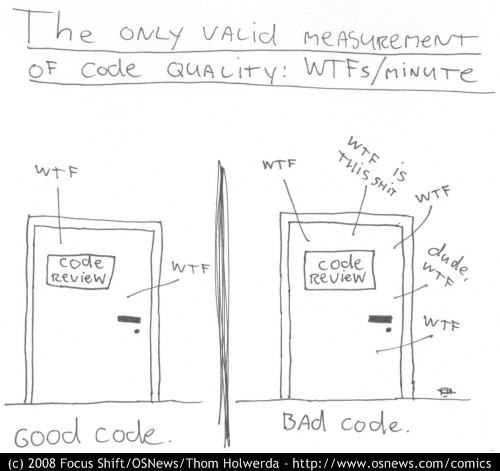

Notes are of different types: small mistakes, remarkable points, key information

and the “interrogation queue”. This queue is inspired by developers’ code review

and the most advanced metric found for it:

- How long is the queue at any point in the paper? Does it introduce too much cognitive load?

- How long is the distance between the appearance of an element in the queue? (the interrogation moment) and its removal (the aha moment)

The second point is easy to solve, just recommend introducing the concept before the place in the text where the interrogation appeared. The first point will require more work on the authors’ side to displace all explanations before the introduction of the concept/symbol, reducing the overall cognitive load at any moment for the reader.

Thematic read & writing the recommendations

After the first reading round, I usually have some ideas about what are the key axes of the review, I can start writing it up with all the small details (typos, clumsy or vague phrasing, etc), all that is not on the structure nor on the content. A good rule of thumb is that those minor corrections are limited to few words in just one sentence. After that, I write down different main axes, as for instance: “this step of the methodology section is not detailed enough” and quote either precise points in the text where the problem arises from and/or recommendations for fixing it: “this or that would make the article to be reproducible”. The deeper a problem is, the more discussion it brings, the goal is not to let the authors stuck with a blind comment, see the following examples nobody likes reading:

“Some steps in Section III seem incorrect”

How much does it cost to the reviewer to point out where and why exactly?

“The authors did not manage to highlight a significant part of the literature”

On which topic? What is not covered? Do you mean the authors did not cite your article?

Only after these last points am I 100% certain of the final recommendation I will give for the manuscript, the usual options are:

- With the minor modifications recommended, the paper is good to be published in my opinion.

- Some required modifications are major, re-submit for another reviewing round.

- The issues raised during review are too central to fix during review rounds, the work needs a huge re-write.

After forming this opinion, if I am not too late on the deadline, I will let myself some time off the review (a few days), and then come back to what I wrote to be sure every comment can be understood and used by the authors to improve the paper. Also, I want to be sure not to have written anything too rash. Nobody wants to be that reviewer.

Conclusion

Even though peer review is considered a pillar of modern research, it has its history, qualities and flaws, and is fundamentally made by human beings and does not systematically reflect a universal truth; that should be kept in mind at all time. Also, the scientific communities should keep challenging it by making it evolve and experimenting new ways of carrying it out, addressing some key flaws. Note that I do not say the solutions presented in these articles are the ground truth, all I am stating is that it is worth opening the discussion, which academia is not doing much at the moment.

Maybe you have other tips for reviewing papers, how do you improve your process? Which points were too domain-dependent / idealistic? (I did warn it was a naive view) Reach out any way you prefer, Twitter, email.

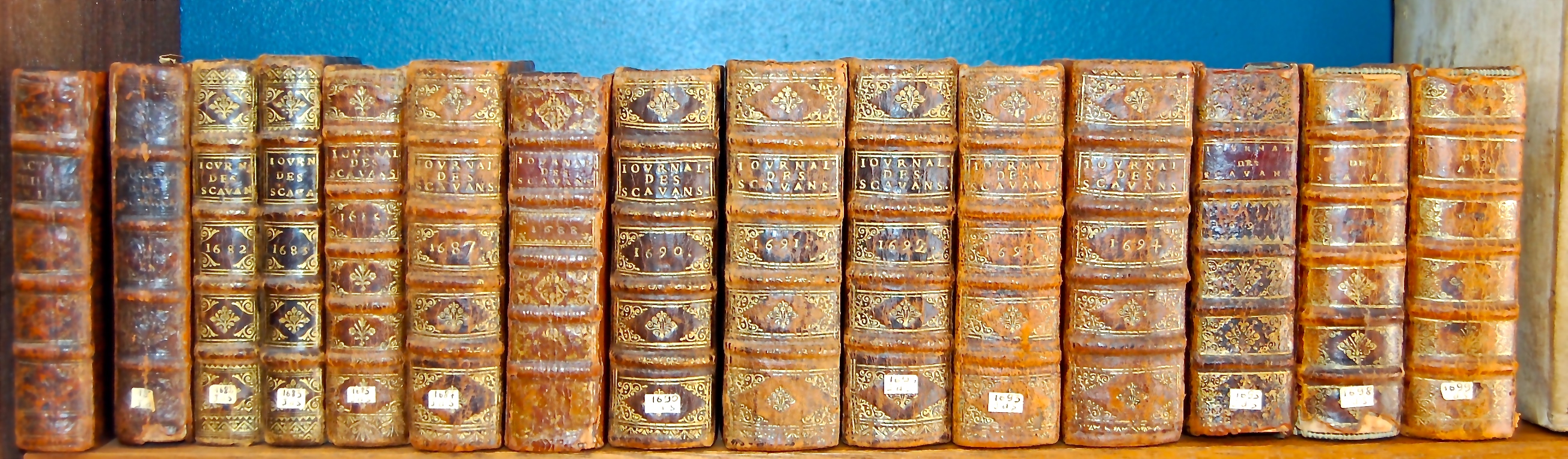

[1] Source for the cover image: Journal des Savants or Journal Des Sçavans in old French, considered the earliest scientific journal. https://jamesgray2.me/2016/09/06/le-journal-des-savants-1681-1699/