Peer review & change highlight

Table of Contents

Last week finished with great news, a paper accepted with minor revisions. With this response came the review of two anonymous scientists, invited by the editor to assess the manuscript and provide feedback and suggestions.

Aside

The number of reviewers can fluctuate depending on your field, on the journal, on the

nature of the communication (conference proceeding, short paper, article).

My personal “highest score” is 8 reviewers on a paper.

The experience was terrible, a huge toll on everyone’s time, in my opinion showing a lack

of peer-reviewing process on the editor’s side.

Whether the required revisions are major or minor, the editor will expect a response from the authors containing:

- the modified manuscript

- some sort of response with how they addressed the reviewers’ comments.

Some sort of response is where differences start to appear between different disciplines and even sub-disciplines.

Academia and the culture of implicit knowledge

We had a discussion with the co-authors on how to convey the changes,

with a disagreement on which would be best. Specifically, I was asked “why don’t you use method X like everyone?”.

Who is everyone? Are we sure that it is the case, even in our sub-field?

The question raises the very interesting point of implicit expectations in the academic culture. Technical know-how is transmitted informally within research groups, from one researcher to the next.

What is expected in a response to reviewers? Some specific points to raise in the letter to the editor? Even one step before, what journal would be a good fit for this manuscript? What are the unsaid characteristics of that journal? There is little, if anything, to find in journals’ guides to authors, which would definitely be an appropriate place for it.

This one-to-one transmission creates very “localized” practices and habits because no one documents these practices but

transmits them informally in informal chats or group meetings.

Why? First documenting beliefs is hard and unnatural in academic writing.

We are used to structuring our written productions so that readers can follow the logical links.

Writing in terms of gut feelings and beliefs is against those principles.

Another reason is that some of this implicit knowledge is not something people would want to be recorded with their name on it.

“That journal has an awful review process” or “this conference has proceedings of varying quality” is something people will happily tell you within a research group but not write in a public note.

Some implicit knowledge is not that controversial but is not a scientific contribution either. Some examples are field-dependent best practices for writing and answering or any content in the sweet spot between graduate-level courses and new research: too advanced to be teachable, but not new to be publishable. In optimization, this kind of content was until recently only covered by few blogs, like Paul Rubin’s or Yet another Math Programming consultant. A new addition is the OR stackexchange Q&A forum and we see from the intense activity that it is covering an existing gap.

“Let’s tear down the implicit on writing practices” has been the motivation for writing this blog post.

Back to manuscript changes

In order to take a broader view and partially remove the implicit aspect, I asked my direct circles how they present the response:

Academic & research twitter, when you send a manuscript after a round of review, you

— Mathieu Besançon (@matbesancon) February 9, 2021

- just send the new manuscript

- add an automatically generated diff (latex diff)

- manually edit the tex source to add colors where things changed?

My Twitter circle is biased towards applied maths and computer science at large and more specifically towards discrete & constrained optimization, applied probabilities and some other areas of computational sciences.

I asked a similar question on a private server with PhD students from more diverse disciplines, received fewer answers but with detailed responses.

I always assumed there is at least a written response to the editor and reviewers with a summary of the changes in the new version of the manuscript. The question is whether there is a version of the manuscript highlighting differences, and how it is produced.

Difference highlight options

I will list below several options. Some of them are in the initial options we discussed with my co-authors. Some are

Colourizing your diff

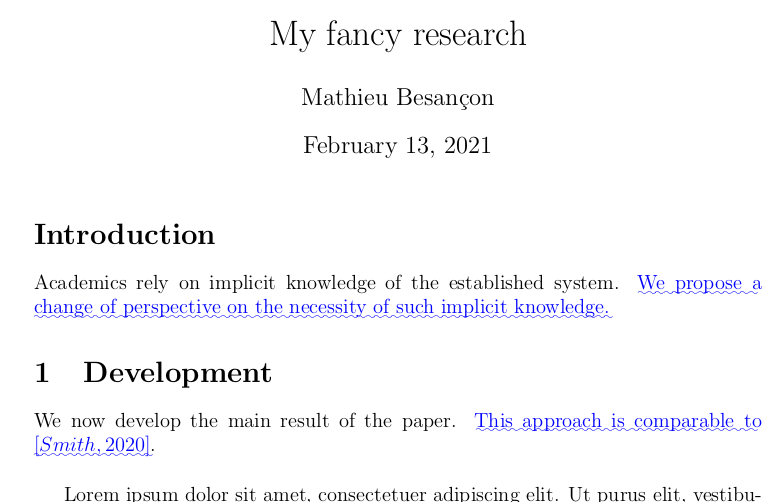

The first option that was presented to me the first time I went through the process is to set a different colour for changed paragraphs so that reviewers and editors can browse through the new version and look at the new paragraphs.

Most article editing software will have some way to do it.

\usepackage{color}

\RequirePackage[normalem]{ulem}

\definecolor{BLUE}{rgb}{0,0,1}

\providecommand{\rev}[1]{{\protect\color{BLUE}\uwave{#1}}}

% in the main body

\section*{Introduction}

Academics rely on implicit knowledge of the established system.

\rev{We propose a change of perspective on the necessity of such implicit knowledge.}

\section{Development}

We now develop the main result of the paper.

\rev{This approach is comparable to [Smith, 2020]}.

with a result looking like the following:

I added the wave underlining to make the diff file print-friendly and readable by colour-impaired people.

The process is fairly straightforward to set up: define a command that highlight changes, and then only use that command to make changes.

What about having a clean version of the manuscript (without colourized highlights)?

Several options there:

- working on the clean version, create a copy with highlight as last step

- working on a version with highlight and remove them at the end

- working on a version with highlight, overwrite the

\revcommand to just output the text for the final version.

Option 1 lets the writer focus on the actual change process without worrying about formatting and highlight before the end. Its other advantage is that you select as an author which part of the changes to highlight, thus guiding the reviewers’ eyes.

But at some point you have to create a split: a version of the manuscript with highlight, and one without. Maintaining two files just means inconsistencies begging to happen.

Option 2 is just a clumsy manual version of option 3. Among possibilities, some colours can remain if you don’t check carefully, words or characters can be removed when the colour is being removed, etc.

The fundamental problem with options 2 and 3 is that the author works on the diff, and then emits the final version with a modification. This means the author sets their eyes on the highlighted version a lot longer, catching misalignments and visual errors, but not the final one, which is the one the author should care about, that’s where the time should be spent.

Having a poorly-formatted highlight file is fine compared to having formatting errors or typos in the actual good version of the manuscript.

Automatically generating diff from versions

If you have your old source files (the version of the manuscript sent for review the first time) or even better if you use a version control system like you should, then it is possible to directly compare versions and emit a visual representation of the changes.

In LaTeX, one tool for this task is latexdiff and its little brother latexdiff-vc.

Of course, tracking everything does not make sense and will probably lead to a visually saturated diff document that can be overwhelming for the reviewers. Luckily, one can always re-generate the diff, this is as cheap as running one command:

$ latexdiff main_old.tex main.tex > diff.tex

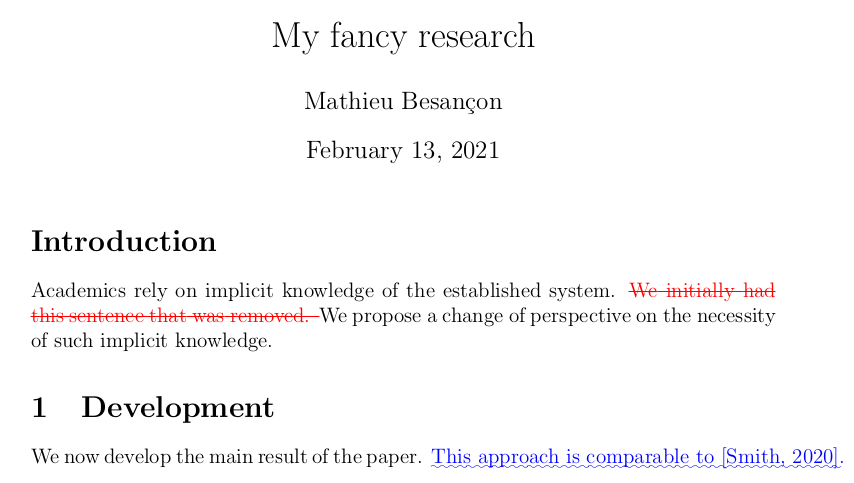

The first thing I do is usually set the deletion behaviour as not showing anything. If you look at the following result of running latexdiff on my example paper:

This is subjective, but seeing both the removed and the added content is not always useful. Most problematic is when some parts were moved, latexdiff will interpret it as an addition and a deletion, which quickly gets bloated.

The drawback is that you need to edit this generated file, so don’t do it before (almost) the end, otherwise there are good chances you will need to re-generate and go through the manual edits again.

What about Word?

Even though Word is seldom used in the mathematics and computer science communities at large, it is the go-to tool in humanities, law, literature and quite present in some engineering domains.

Some people gave me an interesting testimony in that regard: the full diff (using Word revision mode) is not only acceptable even if heavy on the eyes, but it is also the correct way to do it to show the editorial team exactly what has changed since the review. In contrast, I was argued that the generated diff is a “lazy” option because this means not making the effort to show only relevant parts. What if showing the complete diff is a form of transparency on the changes? Indeed, if what is needed is a summary, there is always the explanatory letter on the side summarizing changes and addressing reviewers’ specific comments and questions.

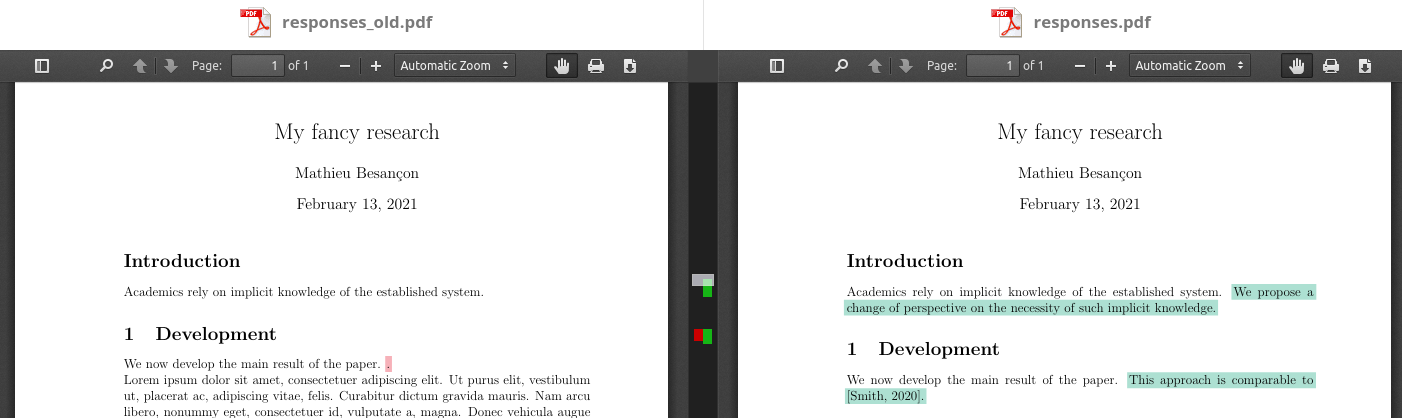

Editing and commenting the generated PDF

An interesting perspective was given by two, users in the answers below the poll: instead of editing the source to highlight differences, change or annotate the PDF, with tools like draftable.

This is definitely interesting to avoid polluting the sources with artifacts from diff highlighting and takes care of the mundane part for you. One drawback could be less flexibility in what can be done to filter or remove highlights in a PDF compared to a source file, but this is definitely worth exploring.

Optional annotation flags

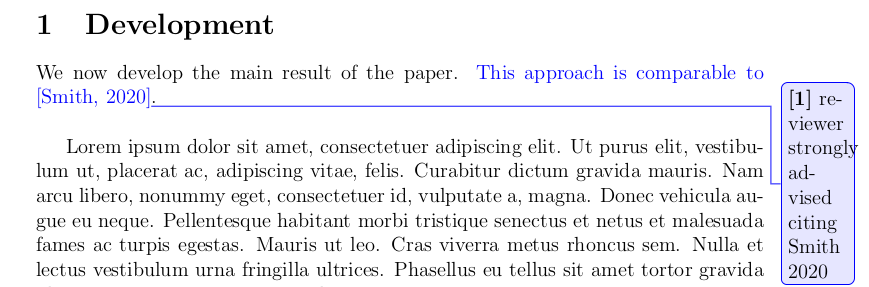

The last option is a variant of manually highlighting your source file but using the changes package. This was recommended by Laura Albert.

The package provides options when importing it:

% highlights the changes

\usepackage[draft]{changes}

% renders the final version

\usepackage[final]{changes}

and then in the text using the modified, added and deleted commands:

\section{Development}

We now develop the main result of the paper.

\added[comment=reviewer strongly advised citing Smith 2020]{

This approach is comparable to [Smith, 2020].

}

with the result looking as follows:

This option is much more robust than keeping raw colours in the text, with just a single point of change (the top-level declaration) between the diff and the final result.

One drawback is that you have to select as you edit what goes in the

displayed modifications and what gets modified without appearing in the highlights.

Otherwise, you need to remember all modifications to add the \added flag.

Still, I think this is one of the viable and reliable options in the whole set presented here, along with an edited latexdiff and possibly PDF edition which I barely tested.

Going to the root: why are we encouraging inefficiency

If you read this post for the tools, you should probably stop there.

One thing that quickly struck me with this particular example of using a slow, manual way because “this is how people do it” is that there is little incentive for academic groups to change time- and cost-inefficient processes.

One weird thing in academia is the many situations where:

- the payer is not the buyer

- the payer is the buyer, but the cost is too low to address the problem

Point 1. applies for instance to the situation of publishing, the university is paying, so academics have low incentive to stop publishing with editors that are enjoying unreasonable margins on public money.

Point 2. is our actual topic. In a labour-intensive industry as many branches of academia are, one thinks carefully about how time is spent. Costs are directly related to that time. It is fairly typical to reason about how much a meeting or a project costs in terms of worker-hours. For sure, research time is hard to assess, sequence, and organize in neat boxes. Why is it not the case in academia?

Why don’t we reason about tasks taking time as a cost center? This might be due to the way people’s time are budgeted in advance: if someone is already working in a lab, their time was funded prior to their arrival and could then be perceived as a sunk cost.

This may also be based on the perception that Master’s and PhD researchers are considered students to some extent. Thus, their activity in the lab is a cost center regardless of the output, since they are in training. Or maybe this stems from academics not being trained in the management of research groups.

But the most direct explanation for low mindfulness of people’s time are the extremely low wage given to junior researchers. A doctoral student makes about 15% of a full professor’s salary in Canada. In contrast, a junior developer is at about 55% the salary of a senior tech lead. We have an odd setting with a labour-intensive industry with a low cost of labour. This can quickly set a low priority on time efficiency, why bother when time is relatively cheap?

One thing to note, I am talking about the academic culture as a whole creating some implicit expectations through the cost structure. It does not mean that all universities share it, but that enough places keep it such that the expectations in the community (like maintaining a time-consuming process for review) are still around.